Revisiting Ownership in Bitcoin

Photograph by Juan Rumimpunu on Unsplash.

People like @vinarmani, and more recently @DustinDry1st, have defended the notion that you cannot own bitcoins [3], [4]. This is met with resistance since it goes against a popular notion of ownership in Bitcoin, and a tradition that goes back to Satoshi Nakamoto and the whitepaper.

I have already written a post describing the concept of ownership in Bitcoin. I want to defend this tradition again by showing that the particular reasoning done by Vin Armani and Dustin Dreifuerst is invalid and by arguing that, in their argument, they ignore that language, as a consensus mechanism, depends very much on the context.

I’ll start with the logic part.

A hidden assumption

The reasoning, supporting their conclusion that you can’t own bitcoins, is made in a slightly different ways. Put simply, they argue that if something is made of parts and you can’t claim something on any of the parts then you also cannot claim that something on the whole. More specifically:

Vin said “If you can’t own UTXOs and you can’t own private keys, you can’t own bitcoins”. Dustin said, In relation to private keys, “no matter how many digits you affix to it, you have no more ownership of it than a reduction of that number to anyone or more parts”.

This reasoning has an underlying assumption that is not proven and therefore, even if the conclusion ends up being true, the reasoning is invalid. You cannot conclude the latter from the former because it is not sufficient. Later I will also argue that the conclusion is not true at all and why.

The underlying assumption, in the presented reasoning, is that the whole is in the same class as the parts and therefore that any property that is valid for the part is also valid for the whole and vice-versa. Intuitively we can think of “class” as a name for a group of things sharing the same properties like “numbers”, of which 1 is a particular element.

To avoid getting too abstract let’s explore some examples.

Simple examples

The simplest way to show what this means is to provide examples for both valid and invalid arguments.

A valid argument, in the same form, could be something like “if 2 is even and 4 is even then 2+4 is even”.

Proving mathematically that 6 is even is beyond the point. What’s required here is to know that “parity” is a property of “integers”, that adding two even numbers results in an even number, and that all 2, 4 and 6 are “integers”. In this example, it makes perfect sense to talk about the parity of 6 in relation to 2 and 4 because it is in the same “class” of 2 and 4.

An invalid argument would be something like “if 2 is even and 4 is even then the point (2, 4) is even”.

In this example we can see that (2, 4), interpreted as the representation of a point in a graph, is not in the same “integers” class as 2 and 4. As a “point” it’s not even correct to talk about its “parity” because points have no such property. With this example we can see that just by combining the parts differently we produced something of a “different” class.

Vin Armani, for example, needs to assume that combining the exclusive knowledge of a private key with the public Bitcoin ledger produces nothing more than another “number”. If that was the case then he could simply have said that you can’t own a number. If that’s not the case then the argument is invalid.

You just need to consider that this combination of parts could produce something different to allow the possibility that ownership is a valid aspect of it. The same way you can consider that a combination of ingredients produces something different, like a meal, and not just another ingredient.

A more visual example

I think Dustin’s formulation requires a different kind of example because, in his post, it is clear that if you’re just adding numbers then the result is still a number, that is, it is in the same class.

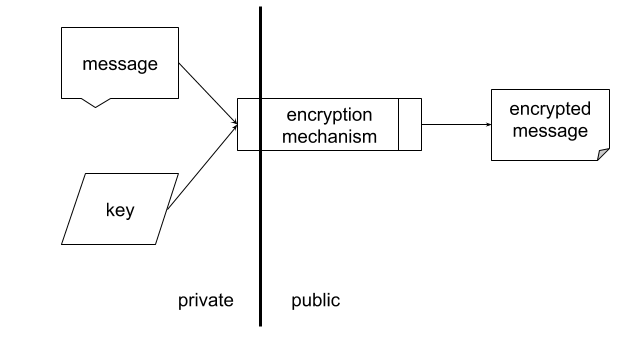

To keep with a theme close to the the original argument, consider the encryption of a message. We don’t need to know details of encryption but only that you also have a private key and there’s a mechanism that takes the private key and a message to produce an encrypted message.

The encrypted message can only be read by someone that has the private key or someone with a powerful enough computer to “break” the encryption, that is, try a lot of keys until they find one that works.

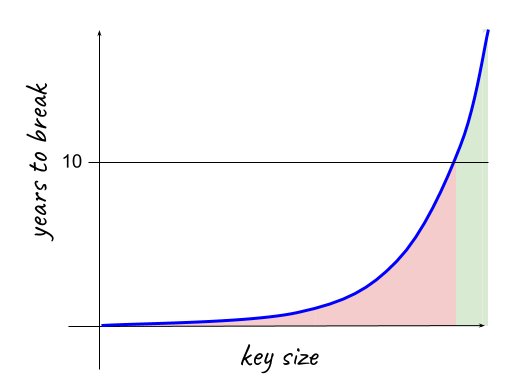

Given that, you can ask “is the encryption secure, that is, can I send the encrypted message over the Internet, for anyone to see, and be relatively sure that no-one will be able to ‘break’ it in the next 10 years”? What you find is that answering that question depends on the size of the key.

A small key is in the class of “insecure keys”. A large key, above a certain level, is called secure or, in other words, is in the class of “secure keys”. In this example, encryption keys are still just numbers but, when combined with an encryption mechanism, they become of a different quality as their size grows. Adding one more digit may be the difference between a secure key and an insecure key. This means Dustin’s argument also fails to account for this possible transition. If the argument is restricted to the math domain then speaking about ownership is meaningless anyway, as that concept does not even exist. But if the argument is made in the Bitcoin domain then you also have to show that all numbers are of the same quality, if you want to draw the conclusion that ownership of the private key is as meaningless as owning a number.

The importance of context

Every language evolves by consensus. It’s probably the first permissionless and decentralized consensus mechanism. But the world has infinite things and we have too few words so we reuse them. A star is not only that thing in the sky but also that person in the stage. You have two legs but so can a race…

Meaning depends fundamentally on the context. Since what separates a context from another is arbitrary, people can and do develop different languages to talk about different aspects of the same thing. For example, when talking about perfumes you can identify a rose by “C6H12O2”, the language of chemistry, or by smelling a “pleasant floral or fruity rose aroma”, the language of fragrances.

What is important here, is that although both languages are valid they are most useful when communicating within their specific context. There’s nothing “fruity” about either geranyl acetate or a rose but the meaning of “fruity” is well defined in the slang of fragrances. To connect with the previous examples, and go back to the main point, saying that an acetate is “fruity” is as nonsensical as saying a point in a graph is even. You can’t just take a word out of context and assume it will have the same meaning.

The language of Bitcoin

The Bitcoin system is still young and is still being constantly redefined but it’s evident that we can talk about Bitcoin and there’s already a specific language for this new domain. We talk about miners, which are not not actual miners, and about a blockchain, which is neither a chain nor formed by actual blocks. Sometimes the meaning of a word changes as more people get involved. The term blockchain started with Satoshi but was already used very broadly, by a large number of people, to describe cryptocurrencies that have no resemblance to what motivated the term. Sometimes even to describe an entire industry. It now seems to be settling on a more generic version of the original meaning, as the majority of people discover other words to use, like “crypto”…

In this context, the meaning of ownership in Bitcoin was never ill defined. It comes directly from the whitepaper so it’s no wonder that the popular notion of ownership is deep-rooted. It’s simple, easy, and useful. It greatly simplifies importing other concepts, like “custodian”, into this domain because their meaning can be easily adapted. As owner of bitcoins you already know it’s your responsibility to protect them. As you transfer them to a custodian you know you’ve given up ownership but also the responsibility to secure them.

This meaning may evolve and the term “ownership” may even fall in disuse, if it proves to be too confusing or simply not useful when communicating. But the arguments presented against the possibility to “own” bitcoins don’t make the claim that the term is not useful, or provide an alternative meaning. Instead, they claim the word is meaningless, that is, that you can’t even claim ownership of a bitcoin.

Crossing domains

It’s perfectly possible to understand the sentence “not your keys, not you bitcoins” without any knowledge of the whitepaper, cryptography, or mathematics. The traditional meaning of ownership is well defined in this Bitcoin context. Therefore, and as mentioned before, it’s important to see if, in the arguments against ownership, the meaning of ownership was imported from a different context. If it was, then we might as well be using two completely different words and claiming they are the same is the confusion.

Let’s take, from Dustin’s article, one of the last conclusions around Bitcoin ownership:

[…] money implies ownership with certain legal rights that in Bitcoin cannot be enforced.

My understanding of what is meant is that Bitcoin can never achieve “money” status because you can’t claim “ownership with certain legal rights” of Bitcoin. But the “ownership” that is used here is a different concept, related with properties of fiat money. We can make a sentence like “you can own a bitcoin but you will never money-own it”, if you’re assuming you’re talking about Bitcoin. By “money-own” I’m referring to the other concept of ownership. If we’re not assuming Bitcoin, as a context, we might say the reverse “money in your hand is protected by certain legal rights of ownership while the Bitcoin notion of ownership grants no such rights”. In this last case “the Bitcoin notion of ownership” is a whole lot of words to say “ownership” if you’re in the Bitcoin context.

Dustin, while never actually being clear about this distinction, does not make the strongest case that you can’t own, in any sense, Bitcoin. The article can just be interpreted, in this sense, as claiming that if none of the historical definitions of ownership apply to Bitcoin then people should understand Bitcoin not as money but primarily as an enabler of greater individual sovereignty, from which money can emerge. It’s in Vin’s video that a stronger claim is made.

If you can’t own UTXOs and you can’t own private keys, you can’t own bitcoins.

Two different “ownerships” are also being used here. In this context “UTXOs” are not in the Bitcoin domain. Previously in the video Vin mentions they just numbers. If they are just numbers they are in the math domain. The private key is a term from the cryptographic domain. Vin also claims it’s just a number so we’re again talking about the math domain. But “bitcoins”, the final part, is in the Bitcoin domain and the audience is assuming that. Besides the reasoning aspect previously mentioned, ownership is being used in the math domain where it is, in fact, meaningless and that meaninglessness is being transported to the “ownership” of Bitcoin as if it was the same concept in the same context.

If we interpret UTXOs and “private keys” in the Bitcoin context, it’s indifferent that they can be decomposed into numbers. The only thing that matters is their properties in relation to people and the Bitcoin protocol. If bitcoins are to be interpreted in the math world then they are also a very long sequence of numbers and ownership becomes indeed meaningless. The problem is in bridging these worlds, taking a word from one, and speak it in the other expecting people to understand you.

Conclusion

Communication is challenging and I’m a believer that it’s of primary importance to understand your audience and meet them where they are. If you speak to yourself, while it may challenge a listener to come closer to you, there can be no reasonable expectation of being understood. And the more you speak to yourself the more people misunderstand you as you create new meanings that are inaccessible.

While I’m making this criticism, I must note that I’m not challenging most arguments. Vin and Dustin’s reflection provides an important insight that may expand people’s understanding of their relationship with cryptocurrencies. More importantly it may guide people into seeking and valuing what is indeed revolutionary in this experiment. But the fact that you can’t own Bitcoin is not that insight and I believe this mutual understanding will help the exploration move forward towards a new consensus and meaning for ownership.