For a Pony, failure is not an option

In the last post I’ve commented that the actor model was well suited for the kind of web applications and services being created nowadays. I’ve also commented that Pony, in particular, was well positioned to allow developing applications that would automatically distribute and scale. More specifically, the aim of Distributed Pony was to allow you to create a monolithic application and have the Pony Runtime automatically identify and distribute the micro-services within (actors, really) through the available resources.

Things fail

Then I’ve read A String of Ponies, by Sebastian Blessing, that felt as one of those movies were you’re told, at the end, that everything was a dream. It’s a good thesis. It shows interesting results and how Concurrent Pony was extended for the distributed setting. It’s major sin, though, was to avoid the big elephant in the room - the failure of a node or the network - until the very end. Even then, just to say the problem was not addressed (which after 70 pages I’d already noticed) and without a credible path for future work.

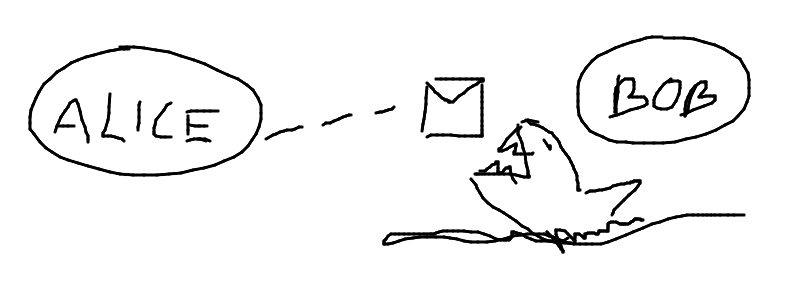

So Distributed Pony is vaporware, right now. It has a prototype that works under unrealistic assumptions. It may have had progress in the last 2 years but the reality didn’t change. The network is unreliable and things fail. Therefore you cannot send a message between actors (that can be in different hosts) and count on it being processed. The message may never reach the destination, the node may have failed, or the response may have been lost.

Dealing with Failure

Erlang and Akka deal with it by giving support for distribution but delegating the responsibility to the user. The topology – what runs where – is managed explicitly by the user that programs the application to launch actors in known nodes. This means the knowledge that something is distributed is explicit and you know that if A fails you can fall-back to B (you have set-up B and coded the application with that scenario in mind).

Still, both Erlang and Akka, give you the functionality to monitor a node and ensure that if a node is unavailable you will always be informed of it. Akka also provides clustering capabilities which, in addition to monitoring, can ensure when a node sees other as down (permanently unavailable) it, and every other node, will never see the node as available again. With monitoring you can fall-back to another actor, with clustering you can ensure failed things remain failed which is important to prevent corrupt, or inconsistent, state from generating errors.

Transparent distribution

So, is it possible to have transparent distribution of a program based on the actor model? Yes, but it may not be practical to make the distribution completely transparent. The semantics of actors are well suited for distribution. Actors only communicate through asynchronous messages which suites well with the need to send the message through the write to another node and with the latency involved in the request-reply pattern. Nevertheless failure must be handled, and complete transparency means you are prevented from knowing which actors will be local or remote. This leaves us three options, to keep transparency:

- We stop the entire program when the failure of a node is detected.

- We take the change of waiting for responses that may never come.

- We consider every actor may be distributed, fail, and must be recovered from.

The first option keeps the distribution transparent because it is the equivalent of a crash in a non-distributed application. The second option is the equivalent of a deadlock. We wait forever for responses from actors, that have unique and non-reproducible state, to avoid assuming the state was lost. The last option has two possibilities. Either we concentrate everything in a single actor – which is transparent about distribution because it is avoided – or we know how to recover from every actor ever launched which will eventually be equivalent to the first option.

The problem, in the last option, is the lack of criteria. Since you can’t know which actors are distributed you have to go for an all or nothing. Imagine the Distributed Pony runtime could be configured to specify which actors could be remote. Even without any changes in the Pony language, and no concept of remote actors, you already would have semi-transparency. The knowledge of the distribution border would make us develop a program that only recovers from those actors that could be distributed. Changing the configuration could introduce errors and take us to one of the first two options again, which means the configuration and the program are not tied and complete transparency was lost.

Future Work for Distributed Pony

So, how can Distributed Pony deal with the failure of the network? I would say that allowing a deadlock situation, due to distribution, is the least desirable property. The last option, which is to leave the programmer assume that every actor may be distributed and fail, is also not practical. This only leaves the option to terminate the entire program. In this case, the runtime would have to detect node failures and ensure a node also fails. It can fail as soon as information of a failure propagates in the tree or as late as possible, that is, when the only other choice is to break transparency. With this failure detection, Distributed Pony would already be pretty useful because if you had 4 nodes you could run two applications (redundancy) and each application in two nodes (distribution). If one node failed then the runtime would ensure one instance of the application would fail entirely, but the other would be independent and unaffected.

Failure detection can also be combined with heuristics for auto recovery, thus avoiding failure. If an actor is stateless or pure, that is, does not have internal state and what it does is process a message and communicate one response, then you may be able to recover from a failure of that actor. The runtime would need to be able to classify those actors and buffer all requests until the corresponding response. If the response didn’t come then the runtime could recreate the actor locally. In this scenario, the work stealing algorithm would probably favour the concentration of such actors in leaf-nodes to reduce the impact of failure from those actors. This could allow applications of the map-reduce sort to expand to a great number of nodes while allowing some node failure or the dynamic expansion and contraction of the lower level the tree of nodes. Nevertheless, the complexity may not be worth the possibly niche case it would cover as it would be impossible to ensure the actor did not produce other side effects while running.

Conclusion

If transparent distribution is supported, and the entire system behaves as one application, we could combine the best of application-level control with transparent distribution. The resources of multiple nodes could be used efficiently and automatically while you ensure redundancy at the application level, as done in many other systems. In this sense the runtime would be at a lower level than in other actor systems, that is, it would deal only with the execution of the actor system. A cluster functionality, for example, would have no place in the Distributed Pony runtime as the distributed application would still be one application bound to work or fail together. Instead, clustering would be an application concept where state synchronization between cooperating applications is important and meaningful.

There are still many areas of improvement that do not require the user to be exposed to the topology of the actors. Some were referred in the thesis, like tuning the work stealing algorithm to account for message-intensive actors. Others were not referred, like ensuring local resources are always opened in the initial node. Without breaking the transparency, there will always be limited options for what Distributed Pony can provide to the user, in comparison with systems like Akka. But maybe that is a good thing. Recognizing that clustering is an application level aspect and that remote actors have different properties than local actors, helps organize applications based on the actor-model better.